���Cheese home

Additional reading

���Sidebar: Big Cheese Rollout

ďż˝

By SUZANNE HAMLIN

From The New York Times

April 22, 1998

Cindy Major still winces remembering her first encounter with Steven Jenkins, who was then the cheese buyer for Dean & DeLuca.

"I left the store and burst into tears," Ms. Major said, recounting Mr. Jenkins's reaction to her homemade sheep's milk cheese, which in 1991 was more the product of beginner's determination than of cheese making skill.

"He spat it out, told me it was terrible, that, like all American cheeses it had no flavor, and never, ever to bring him a cheese like that again,", she said. But she managed to carry on. Now, at 34, she and her husband, David, are among America's most successful artisanal cheese makers, turning out an aged sheep's milk cheese at their farm in southeast Vermont that some connoisseurs will reach for before one from France or Italy.

The cheese, Vermont Shepherd, is described as "spectacular, an American treasure" in "Cheese Primer" (Workman Publishing, 1996), a guide to the world's cheeses written by the very same Mr. Jenkins. It has been anointed with awards and is sought after by cheese merchants. Neal's Yard Dairy in London has asked to sell it, starting this year if all the arrangements can be made, which would make it the first American product at that prestigious shop.

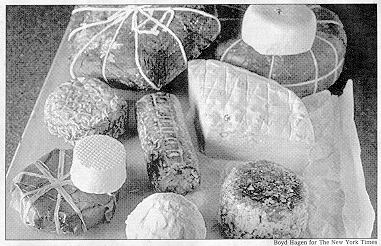

Local Flavors American cheese at Murray's cheese shop, clockwise from top right: Brier Run banon atop Sally Jackson sheep's milk, Old Chatham Sheepherding Company tomme, Brier Run Banon with herbs, Capriole Wabash Connonball, Coach Farms Button atop Capriole Banon, Westfield Farms Hubbardston Blue, Sally Jackson goat cheese and, at center, Westfield Farms Blue Goat Log. |

But the Majors's cheese does not stand alone in excellence. These days, milk is, to borrow Clifton Fadiman's phrase, leaping toward immortality in Indiana, West Virginia, California, Massachusetts, Washington, Oregon, Iowa, Illinois, Louisiana and Texas, as well as in the traditional dairy states of Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, New York and Vermont.

In the United States, there are now some 200 small, independent producers, compared with just a handful in the 1980's. Although the last 25 years have seen gradual growth in the production of, and interest in, the kinds of cheeses they make, Laura Jacobs-Welch, administrator of the American Cheese Society, an artisanal association, said consumer interest rose stunningly in the mid-1990's. As in France, the cheeses are regional; their greatest early support came from local farmers' markets, and the alliance continues today.

"What we know is that because of travel, restaurants and well-informed retailers, the American palate has really grown up," Ms. Jacobs-Welch said. While the European classics like Stilton, Brie de Meaux and Roquefort are in no immediate danger from the competition, the American makers have clearly benefited from the increased appetite for cheeses from all over the world.

Americans are coming to understand the qualities of good cheese. A great cheese talks back. It is memorable. It makes you stop and consider it, as wine does. It does not have a single note: there should be dimensions of discernible flavor and texture.

Americans now eat, on average, 30 pounds of cheese a year each, compared with about 17 pounds a year 20 years ago. It is impossible to tease out the proportion represented by American artisanal, or farmhouse, cheeses, because the Government keeps records only by standard categories, like Cheddar and mozzarella, which do not fit many of the new American cheeses. But evidence of their growing popularity can be readily seen at fine cheese. stores and restaurants. At Formaggio Kitchen in Boston, which usually has 250 cheeses on hand, as many as 30 are now American farmhouse cheeses. Three years ago, the shop carried fewer than 10, and Matthew Rubiner, the cheese buyer, says he wasn't particularly proud of those. These days he displays artisanal cheeses front and center.

At Gramercy Tavern in Manhattan, the daily cheese selection of 16 to 18 varieties includes 3 to 6 that are small-farm American products, like Wabash Cannonball, a Capriole in Greenville, Ind.

In all the hubbub, restaurants are trying to get smarter. Mr. Rubiner began offering a crash course on cheese for restaurants two years ago. "We now have 55 accounts around the country," he said. "None of which we solicited."

In America, as in Europe, sheep and goats raised by cheese makers themselves produce the most favored milk. A maker has more control over the product and the final result often has more character than a cow's milk variety, which is usually commercially produced and blander. Sheep's milk is sweet and delicate. The milk of goats is feisty, with an acidic tang that tends to give it a more aggressive flavor.

Beyond the choice of milk, American farmhouse cheeses differ from those of the big producers in both subtle and obvious ways. The most important is that they are not produced on an assembly line. Every cheese gets individual attention, depending on variables affecting the milk, like weather or the location of the pasture (which is intentionally altered from time to time on each farm to avoid depletion of the fields).

The commercial rule book may say that a fresh goat cheese requires six weeks of aging, but an artisanal cheese maker might decide, on inspection, that a particular cheese needs eight weeks. The intricacies of aging are regarded among cheese makers as the ultimate art. There is also a personal connection between cheese maker and cheese buyer; often, farmhouse cheeses come with a note on how long they were aged, what the animals were fed and more.

Another personal touch is the attention to pasteurization. Milk for farmhouse cheeses is usually pasteurized more slowly than for commercial cheeses, and at a lower temperature to avoid the "cooked" taste.

Farmhouse cheeses made from sheep's milk are seasonal. The ewes' milking time is in the spring, right after their lambs are weaned, so some of the best sheep's milk cheeses are not always available. Aged cheeses are usually ready four to six months after milking, with nonaged varieties ready within weeks. (Goats give milk year round, so the season is not a factor.)

The range of artisanal cheeses is wide: there are blues and rustic country cheeses; soft, semisoft, firm and grating cheeses. There are logs, wheels, pyramids, disks, cones, buttons, sticks and bricks. Some are based, on classic cheese formulas, others wildly or mildly innovative. The Amawalk of Egg Farm Dairy in Peekskill, N.Y., for example, resembles fontina and Gouda, but it is denser than either, and more rustic. The variability from cheese to cheese (even when they bear the same name) is part of the charm.

Are the new regional cheeses a bargain?

In dollars and cents, no: most cost $8 to $20 a, pound, versus $6 a pound or less for commercial cheeses. But they may be the best in American markets, because some cheese makers in France, Spain, Italy, England and Switzerland do not export some of their most interesting varieties to what they see as an unsophisticated American market.

Debra Dickerson, the United States representative for Neal's Yard Dairy in London, said: "European cheese makers often hold back their deeply pungent, full-flavored cheeses. Even now, they just don't believe that the American palate would be appreciative."

But some Europeans who come to America find that they prefer the regional cheeses produced here. "I have French customers who only buy American - Old Chatham's Camembert and Vermont Shepherd," said Bob Johnson, a salesman at Murray's Cheese on Bleecker Street. "And they definitely prefer Humboldt Fog to any of the imported ch�vres."

Humboldt Fog is an exceptional goat cheese, with a creamy, translucent exterior and a texture that grows increasingly dense toward the center. It has a touch of acid that is muted and made richer by the aging process, and lacks the sharp aftertaste of many goat cheeses. A slender layer of vegetable ash runs horizontally through the center, similar to that in classic Morbier, introduced for its subtle texture and flavor.

Made at Cypress Grove Ch�vre in McKinleyville, Calif., it is named for the foggy weather on the rocky redwood coast where Mary Keehn, "a single mom with. a small child," began making cheese from the milk of a few goats 20 years ago.

"I knew nothing - I just liked to cook," Ms. Keehn said. She traveled to France, worked with and sold to local restaurants, never stopped experimenting ("just like cooking, you learn all the rules and then you break them") and now is in partnership with her daughter, Malorie McCurdy.

Others jumped more precipitately into cheese making like David and Cindy Major of Vermont Shepherd, who got their start a mere 10 years ago. "We were idiots," said Ms. Major, who set out to save the family homestead, a hilly, nonworking 250-acre farm that came with a flock of pet sheep. "We didn't even know you could milk sheep."

In 1983, just home from Harvard University with degrees in engineering and medieval studies, David Major, fearing that his parents' land could become Mall City, began to read about dairy farming.

"We started with an old book we bought at an ag fair," said Ms. Major, a Manhattan native whose father, Charles Schwartz, owns Elmhurst Dairies on Long Island, a onetime milk bottler that is now a distributor.

With support and advice from other Vermont cheese makers, the Majors began milking and then, in 1989, making cheese. But it was only after a learning trip to the great French mountain cheese region in the Pyrenees that "we realized we were doing everything wrong," particularly in the aging process, Ms. Major said last week, standing in the new aging cave, at the Vermont Shepherd Farm in Westminster West, Vt., near Putney.

The 1997 supply of rustic, eight-pound rounds of Vermont Shepherd is nearly depleted. But next week, the 80 sheep that recently gave birth to lambs will start being milked twice a day for the 1998 cheese. The new cheeses will be nurtured and observed in the cave for four months, sampled periodically by a small panel of cheese professionals.

Vermont Shepherd cheese has its own character, a result, in no small part, of the Vermont pasture herbs and grass where it begins. Firm but moist, buttery, pale yellow and shaped like a hard-crusted I round of country bread, Vermont Shepherd has a, gentle nonacidic tang and a rich, complex, almost nutty flavor. It's a mountain cheese worthy of any knapsack, but it's an after-dinner cheese, too, for savoring in small bites.

An abiding confusion among people trying to enjoy American cheeses is the tendency of some producers to give them European names, like Camembert or Brie, rather than labels that convey their own distinctions. (Such familiar names can, however, offer an approximate guide to flavor.)

Ms. Dickerson, of Neal's Yard Dairy in London, pointed out that the Old Chatham (N.Y.) Sheepherding Company's Camembert is not really Camembert. It is made from sheep's milk, while the genuine Normandy article is made from cow's milk. Although both are soft and mold-ripened, the Old Chatham cheese is milder and the French version has more chalkiness at its center (which the French admire). Ms. Dickerson said the Old Chatham is delicious, but "it's its own thing." She said she would prefer some creative new name, like the one Old Chatham gave a soft goat cheese that it makes in little rounds: Button Mutton.

But without familiar and distinct references to guide the consumer, and in the absence of a new

cheese vocabulary to assist, it is hard to know much without tasting the cheese first. It's a good

idea to taste before you buy - so seek out a good purveyor, and let the adventure begin.

FIN